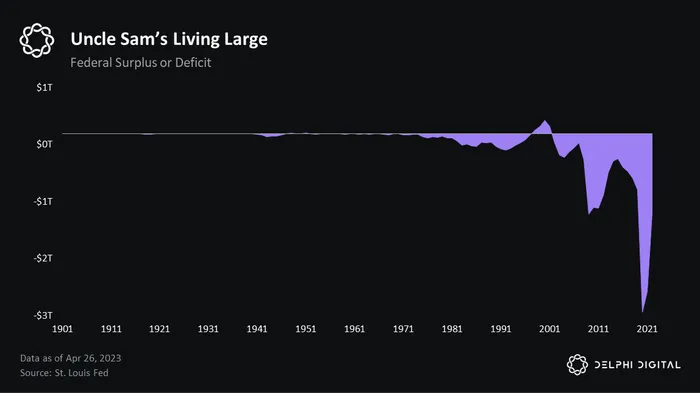

The U.S. government spends more money than it makes. This is, of course, obvious as it’s been this way since the 1970s — and that’s being generous…

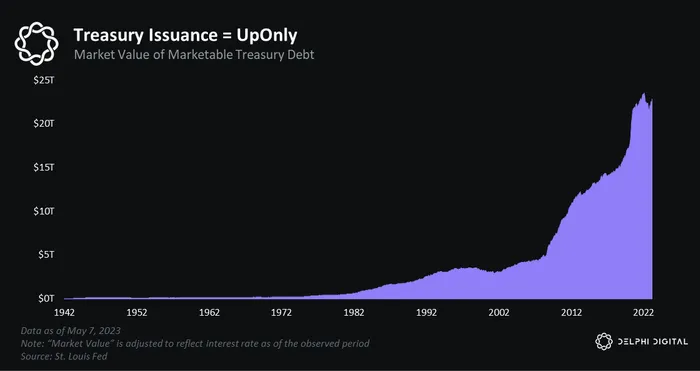

To fill the yawing gap between receipts and outlays, the good ole U.S.G. shills Treasuries: debt securities issued by the U.S. Treasury Department. Treasuries are considered the safest investment on planet Earth because they’re backed by, uh, this:

As the U.S. deficit has grown and Americans have taken to liking moar free stuff — healthcare, stimmies, etc — the Treasury has been forced to issue moar debt to keep up with politicians’ checkbooks.

At this point, it might sound like the Treasury is just at the whims of their more famous compatriots: elected politicians. But that’s not the case. Treasury officials are intimately involved in all facets of economic decision-making. And despite the impulsive spending habits of politicians on both sides of the aisle, the Treasury Dept actually plans its security sales well in advance, typically several months to a year ahead of time. In fact, it’s even nice enough to publish a quarterly refunding statement, which outlines its borrowing needs for the upcoming quarter, including the expected amounts and maturities of Treasury securities to be issued.

So we shouldn’t feel too bad for Treasury. It’s not like Joe Biden walks over to Janet Yellen’s office on a Monday and says, “hey Jan, we gotta issue anotha $10 billy wop asap to fund my new ice cream, err, infra bill,” and then expects the debt to be sold the next day on Tuesday. That’s just, uh, not how it works.

As the current debt ceiling showdown proves, government processes that involve big-time moolah are longggg, slow-moving and involve many parties; chief among them is the U.S. Treasury, which is essentially the entire USG’s sugar daddy.

Anyways, the point is, if Treasury officials were smart and, uh, acting in the best interest of yanno we the people, they would aim to issue a lotta debt when interest rates are low and issue the bare minimum when rates are high. Most people like to “buy low and sell high,” but the Treasury wants to invert that formula and “sell low and buy high.”

Obviously, hindsight is 20/20, and it’s easier said than done. After all, it’s not like the Treasury’s singular customer — the U.S. gov — can, like, wait to pay its bills.

But the point still stands: the well-functioning Treasury Dept should be actively looking for opportunities to save taxpayer money.

Unfortunately, that’s not happening.

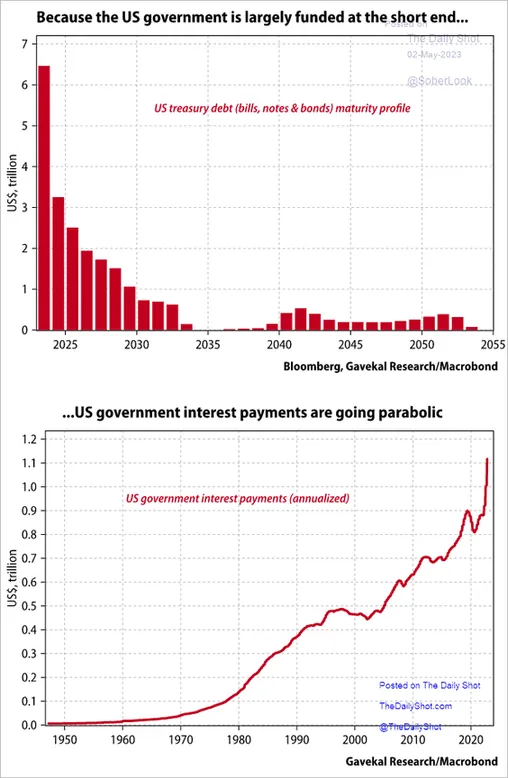

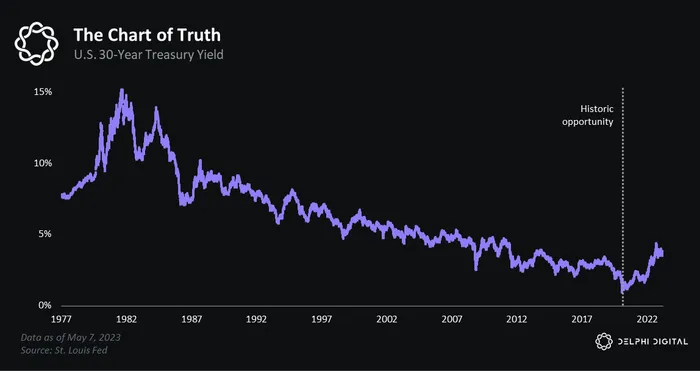

As the chart above makes clear, the federal government completely whiffed on locking in historically low long-term rates during 2020-2021. Now, the Treasury’s decision to stick with its modus operandi is coming back to bite us all as interest payments surge due to the Treasury’s exposure to rising short-term rates.

What’s happening is simple, really, except I guess if you’re at Treasury, Instead of shilling something, idk, crazy like a 100Y bond offering a 2% yield during Covid — a yield that would have considered juicy at the time — the Treasury opted to continue its practice of selling bonds with shorter duration, amplifying its exposure to the short end of the curve.

From the Covid trough to the pre-banking crisis peak, the 2-year yield went up 42x. That’s $h!tcoin territory! Unfortunately, mooning short-term yields isn’t something anyone will be bullposting about on CT. That’s cuz higher short-term rates raise the Treasury’s borrowing costs, which is, like, no bueno for all of us owners and governance members of the ponzi project known as the U.S. government.

The issue is that the Treasury has always opted for short-term over long-term debt. They, like many bureaucrats, are shockingly inflexible. However, there are a few semi-logical reasons for its historical preference for short duration:

- Lower interest rate risk– less bad stuff can happen in 2 years vs 30 years

- Lower issuance costs — interest rates are lower on 2Y bonds vs 30Y bonds

- Greater liquidity — short-end rates tend to be more liquid than long-end rates

These are all, like, valid and understandable reasons why the Treasury, in normal times, would generally prefer short-term over long-term debt issuance. But 2020 and 2021 were not normal times! They were many things, but “normal” is not one of them.

So, in my armchair expert opinion, the fact that the Treasury didn’t take full advantage of prolonged negative real rates is a damning indictment of just how rigid, myopic and obsolete U.S. monetary policy has become.

Our research indicates that this latest Treasury faux pas is unremarkable. It fits a long pattern of mismanagement and kicking problems down the road. The biggest problem on the near horizon is our interest payment problem.

Currently, interest payments make up 10% of all government revenues aka taxes. By 2035, this figure is projected — by the government itself — to jump to 21%. And by 2050, interest payments will account for a stunning 45% of all government revenue.

The Treasury Department knows these numbers better than anyone, which makes it even more confuzzling why they didn’t back up the Brinks truck and turbo dump some 100Y bonds — or something similar — onto a yield-starved market.

The only reasons I can think of for why the Treasury didn’t make such a move are:

- One, they thought rates would go downonly / stay ultra-low forever

- Or two, they were too set in their ways to try such an avant-garde move

Personally, I’m not sure which is worse.

Alas, Brad Gerstner — a noted hedge fund manager — recently made waves by singling out the Federal Reserve for its Covid-era incompetence: a point I thought viewed as axiomatic. He called for a “Manhattan Data Project. It’s a good idea and one it seems the Treasury could benefit from as well.

But what if we didn’t need some heroic, hail-mary Manhattan Project? What if the solution was right here in front of us?

No, I don’t mean the bird app, err, Twitter 2.0, err, X. Even an everything app won’t do. What we need is a whole paradigm shift.

A way to encode monetary policy in the world of bits, thereby making it algorithmic, transparent, trustworthy, flexible and dynamic.

If only…