When Jerome Powell issues his imminent decree, he will weigh two competing forces: the deflation emanating from the banking sector and the Fed’s inherently inflationary response.

“Jerome Powell as Thanos” – Midjourney

People like to throw around the word “recession” as if it carries mythical powers. The truth is, it doesn’t. Even when economies enter a recession, banks continue to lend; people continue to borrow; and the economy chugs along. There’s just, uhh, less excitement and activity on all fronts.

Until recently, one key difference between the 2007-2008 Great Financial Crisis and our hotly debated current ‘recession’ was the banking sector’s health. In 2007, it was the banks that caused the recession.

In 2023, many were predicting a recession despite a robust banking sector. The banks appeared healthy and were functioning fine. Credit continued to flow, and the economy gradually slowed but kept chugging.

The events of the past two weeks have upended this goldilocks narrative.

When the banking sector falls under duress, banks (logically) stop lending; they husband their cash for fear they, too, might get run.

Source: Court Hoover

And when banks stop lending, the economy grinds to a halt – especially the credit-driven U.S. economy.

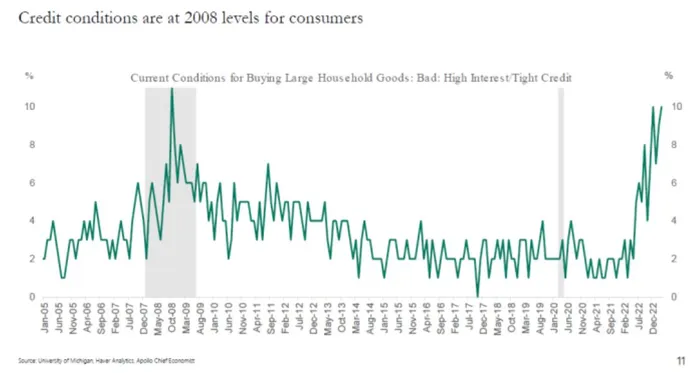

“The University of Michigan consumer survey on credit conditions found that even before the SVB debacle, credit conditions had tightened to levels last seen in 2008.” – Torsten Slok, Apollo

As Alexander Campell notes, in a piece titled Remember Folks, Banking Crises are *Deflationary,*:

“Of the ~20 or so deflationary episodes in the last 200 years, 15 were a direct result of a financial crisis.”

Source: Alexander Campbell

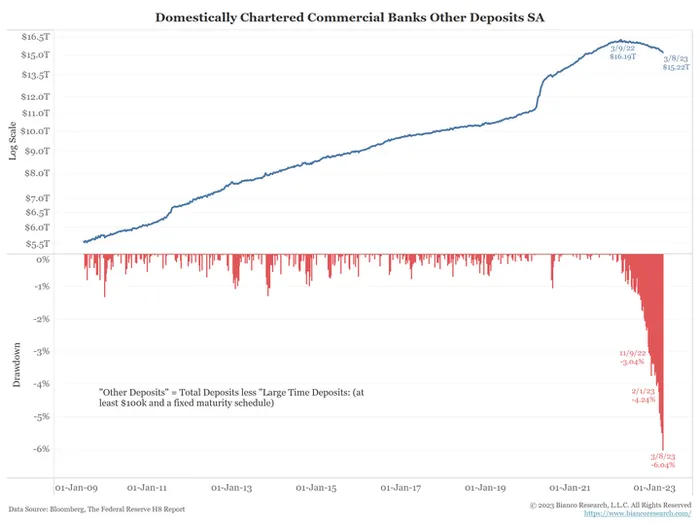

The Fed – always a student of history – was rightly freaked out over the possibility of the U.S. banking system collapsing for the second time in 20 years. So they responded by introducing the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP). This program was designed to give the banks access to liquidity (dollars) to meet customer withdrawals.

Source: Jim Bianco

An oversimplified but not entirely wrong way to think about BTFP is as follows:

- Banks send collateral to the Fed (U.S. Treasuries, Mortgage-Backed Securities)

- Fed sends dollars back to banks

- Banks use dollars to meet customer withdrawals

- Some percentage of banks use some percentage of Fed dollars to issue fresh loans / make new securities purchases

The high-level outcome of BTFP will be an injection of liquidity into the market as the amount of money created by the Fed, and the number of dollars in circulation both grow. To be clear, the Fed is now conducting quantitative easing (QE) under another guise.

The Fed limited the scope of BTFP to the total size of the UST and MBS held by U.S. banks, approximately $4.4 trillion. Notably, $4.4 trillion is more money than the Fed printed in response to COVID when it unleashed $4.189 trillion on a shutdown economy.

Going forward, the Fed will be forced to weigh the impact of its QE-like program (BTFP) — which will likely be constructive for asset prices — against its stated desire to continue battling persistent inflation. During Powell’s comments, investors will be listening to better understand his thinking on this apparent contradiction in the Fed’s monetary policy.

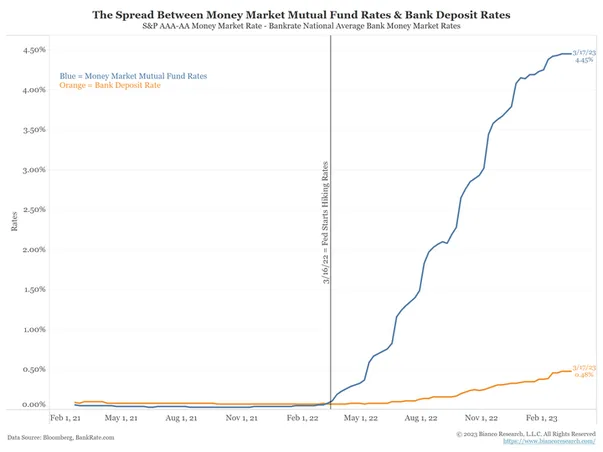

Investors will also be keying in on the Fed’s plans for future rate hikes. Here, the Fed finds itself comically constrained by yet another contradiction. Every time the Fed hikes going forward, the spread between what depositors can earn at their bank versus what they can earn lending to the U.S. government (buying USTs) will widen. Subsequent rate hikes will give depositors even more incentive to leave, and the banks will continue to bleed deposits and require even more help from the Fed.

Expect Powell to signal or at least hint at a pause as the Fed’s current posture appears untenable.

Expect Powell to signal or at least hint at a pause as the Fed’s current posture appears untenable.