The basic model of a bank run goes like this:

You’re a bank and you get $100 worth of deposits. You turn those deposits into $100 of rock-solid loans and $20 cash sitting in yo Gringotts-style bank vault. One day, your depositors show up and demand all their money back. You don’t have it.

You have $20 cash and they want $100. But you’re good for it. You’ve got $100 of pristine loans just sittin on da books and when you get paid back, you’ll have plenty of money for your depositors. You’re just not good for it right now. If you had more time, your $120 of assets would more than cover the $100 of liabilities. You are illiquid but solvent.

On the other hand, if you have $100 of loans and $20 of cash, but $40 of the loans were made to a, uhh, institution called ‘XTF’ that is, like, running an international ponzi scheme, then you’ll have to write down the value of the loans to $60, leaving you with only $80 worth of assets.

If your depositors demand all their money back, you’re screwed. You don’t have it. But that’s not even the main problem; the main problem is that even when the rest of the loans are paid back, you’ll only have $80 and owe $100. Your assets are worth less than your liabilities. You are illiquid and insolvent.

In this second case, the bank has more liabilities than assets. They are donzo and literally going to zero. Nighty night!

However, in the first case, the bank has more assets than liabilities. The only problem is there’s a duration mismatch — i.e. “sorry we don’t have your money today, but come back, like, next week and we’ll have it then. If the bank can just convince its depositers to chill out, then all will be okay. But depositors are not chill, they’re panicked and they want their money now.

Silicon Valley Bank ($SIVB) falls into this second bucket. It’s illiquid but solvent. At least it was at the *beginning…

To understand how Silicon Valley Bank found itself in this mess, we must revisit what boomer banks do for a living.

Traditional banks take deposits and make loans, like the two examples above. When a bank makes a loan, they take credit risk. The risk the bank assumes is tied to the creditworthiness of the borrower. If you’re lending to Warren Buffett, your credit risk is low. If you’re lending to Sam Bankman-Fried, your credit risk is, uhh, higher.

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) is not a traditional bank. It’s a startup bank. It has a completely different customer base than a ‘traditional bank.’ SVB’s customer base is made up of companies working on, like, the metaverse, while a traditional bank’s customer base is made up of companies making, idk, widgets?

Anyways, the point is: SVB’s customers were not asking SVB to earn them super duper high yields. They were just looking for a place to park all dat cash they got during the venture funding boon times of 2020 and 2021.

As a result, SVB was not using its deposits to make loans, it was using them to do something even safer: buy bonds. You know, government bonds aka the assets people pretend are “risk-free.” Well, as it turns out, bonds do carry some risk, specifically they carry interest-rate risk.

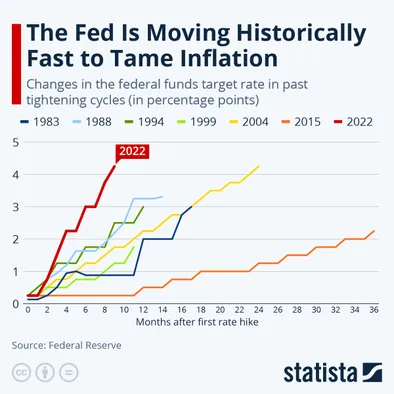

Instead of making loans to risky corporate borrowers like XTF, Silicon Valley Bank bought long-term bonds backed by the good ole U.S. government. Tragically, SVB bought these bonds at the pico top of a generational bull run, right before the Fed embarked on an unprecedented hiking schedule. Most banks, when interest rates go up, have to pay more interest on deposits, but get paid more interest on their loans, and end up profiting from rising interest rates. But SVB, as the banker of metaverse companies, owns a lotta long-duration bonds, and their market value goes down as rates go up.

Most banks, when interest rates go up, have to pay more interest on deposits, but get paid more interest on their loans, and end up profiting from rising interest rates. But SVB, as the banker of metaverse companies, owns a lotta long-duration bonds, and their market value goes down as rates go up.

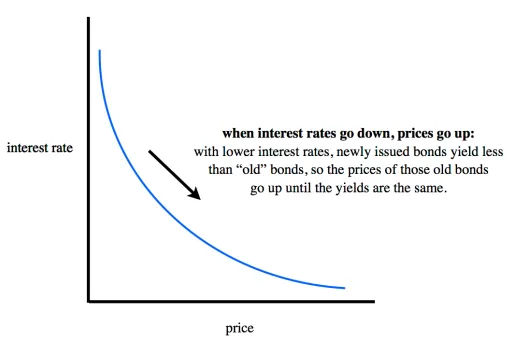

Visually, the relationship looks like this:

Critically, when interest rates go up rapidly, if your assets are all long-dated bonds, they will go down in value. Banks typically deal with this risk by holding their assets to maturity and not marking them to market: if you have a 10-year bond and interest rates go up, the bond’s market value goes down, but if you just wait 10 years you’ll be repaid in full and it’s no problem.

Silicon Valley Bank, however, doesn’t have 10 years. It needs liquidity today in order to satisfy panicked depositors. So, SVC is in a bit of a pickle. On paper, SVB is illiquid but solvent. But its solvency status could quickly change depending on the magnitude of withdrawals. Once SVB has to liquidate its bond portfolio at a loss (thanks Jerome Powell!) then its status could quickly change from illiquid but solvent, to illiquid and insolvent.

It appears this ‘insolvency rubicon’ has already been crossed, at least across the pond in the U.K.

How SVB’s U.K. arm influences the U.S. parent company is unclear. But what is clear, is that SVB is in serious trouble, mostly due to it’s unique liabilities risk profile. The Financial Times reports:

Few other banks have as much of their assets locked up in fixed-rate securities as SVB, rather than in floating-rate loans. Securities are 56% of SVB’s assets. At Fifth Third, the figure is 25% ; at Bank of America, it is 28%.

For most banks higher rates, in and of themselves, are good news. They help the asset side of the balance sheet more than they hurt the liability side. … SVB is the opposite: higher rates hurt it on the liability side more than they help it on the asset side. As Oppenheimer bank analyst Chris Kotowski sums up, SVB is “a liability-sensitive outlier in a generally asset-sensitive world.”

In a weird way, Silicon Valley bank is a victim of Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP). “One of us!” shouts downbad magic internet money hodlers…

Remember SVB’s bread and butter was/is servicing startups. Startups are, in some ways, a function of ZIRP. When money is free, a dollar 20 years from now is worth the same as today. So in a ZIRP world, investors love startups, as was the case in 2021.

Here’s how SVB Financial Group, the holding company of Silicon Valley Bank, describes the vibe of 2021 and 2022 in its Form 10-K two weeks ago:

Much of the recent deposit growth was driven by our clients across all segments obtaining liquidity through liquidity events, such as IPOs, secondary offerings, SPAC fundraising, venture capital investments, acquisitions and other fundraising activities—which during 2021 and early 2022 were at notably high levels.

For SVB, being in the startup business is highly reflexive. When rates are low, startups throw a ton of cash at you, which you use to make a concentrated bet on interest rates. But when rates go up, your customers get smoked (what even is the metaverse?) so they withdrew their deposits, forcing you to sell those securities at a loss to pay them back. Now you have lost money and look financially shaky, so customers get spooked and withdraw more money, so you sell more securities, so you book more losses, yada yada yada.

Yesterday, regulators closed Silicon Valley Bank and took control of its deposits, in what’s being described as the largest U.S. bank failure since the global financial crisis more than a decade ago.

According to press releases from regulators, the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation closed SVB and named the FDIC as the receiver.

Whether depositors with more than $250,000 ultimately get all their money back will be determined by the amount of money the regulator gets as it sells SVB’s (underwater) bond portfolio.

As with all bank runs, more withdrawals means more underwater asset sales, resulting in a growing realized hole.